Could an Anonymous Path to Mental Health Help Prevent Military Suicides?

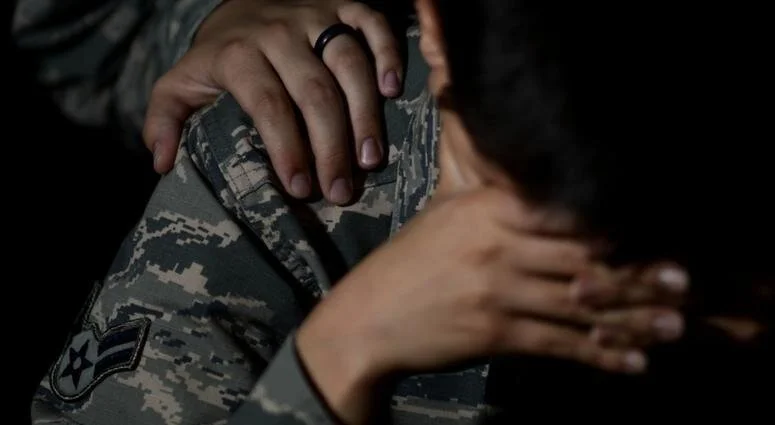

U.S. Air Force illustration by Airman 1st Class Kathryn R.C. Reaves

Military and veteran suicides continue to rise, despite billions in federal funding and ever-expanding programs and resources.

About 20 veterans die by suicide daily. Active-duty suicides in 2018 were the highest since the military began tracking the numbers in 2001.

"The results" of suicide prevention efforts so far "are not nearly enough," said Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

On Wednesday, members of Congress wanted answers. They didn't exactly get them, but they did posit a potential path for service members to get help while easing the fear of jeopardizing their careers.

Gillibrand and Chairman Sen. Thom Tillis, R-N.C., the heads of the Senate Armed Services Committee, asked military, veteran and civilian mental health experts if it could be possible for troops to report and seek help for mental health concerns without their bosses finding out and risking their jobs or advancement.

Richard McKeon, suicide prevention branch chief at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, told Congress that only about 20-25 percent of people who die by suicide had recent mental health treatment.

Gillibrand said she wanted to know if there is a way to create an anonymous "continuum of care for mental health outside the chain of command, so there is not that fear of being degraded, devalued or sidelined."

Tillis said the Defense Department needs to do more to prevent troops from facing a "stigma" for seeking mental health help.

Gillibrand said the military must look at granting service members anonymity for surveys to determine mental health overall and for individual mental health services "throughout their career."

Currently, service members can go to military chaplains and be granted anonymity in most cases. But that is not the case for seeking mental health help with a counselor or medical provider, Defense officials and members of Congress said.

Gillibrand likened it to the military's process to allow anonymity in reporting sexual assault.

"We need to look at how to create a safe space for mental health reporting, similar to reporting sexual violence," she said. "The requirement by the chain of command to report mental health issues can be a significant barrier to seeking help."

Karin Orvis, director of the Pentagon's Defense Suicide Prevention Office, said the department is "trying to change the culture around help seeking" and developing a training program "focused on talking about the concerns service members have" in reaching out for help, including "impact on security clearance and privacy concerns."

"Clearly our rate (of death by suicide) shows more needs to be done," said Capt. Michael Colston, director for mental health programs at the Defense Department.

While an anonymous path to care may assuage some service members' fears, the Defense Department already is struggling to keep enough mental health professionals around to treat the troops currently seeking services.

DoD, like VA, has struggled to recruit and retain qualified mental healthcare providers because of lower pay, high workloads and fewer opportunities for advancement, according to the Pentagon.

"Suicide is not caused by a single condition," Gillibrand said. "Lost in the research reports are the stories."

"There's not going to be any one solution," Tillis said of deaths by suicide among veterans and the military. "It's an effort that will continue for many Congresses ... Maybe we could codify one little thing so command understands how they should behave."

By Abbie Bennett | Published by ConnectingVets | Read the article